Rick Clark's Music I Love Blog: Gus Dudgeon on Elton, Part 2

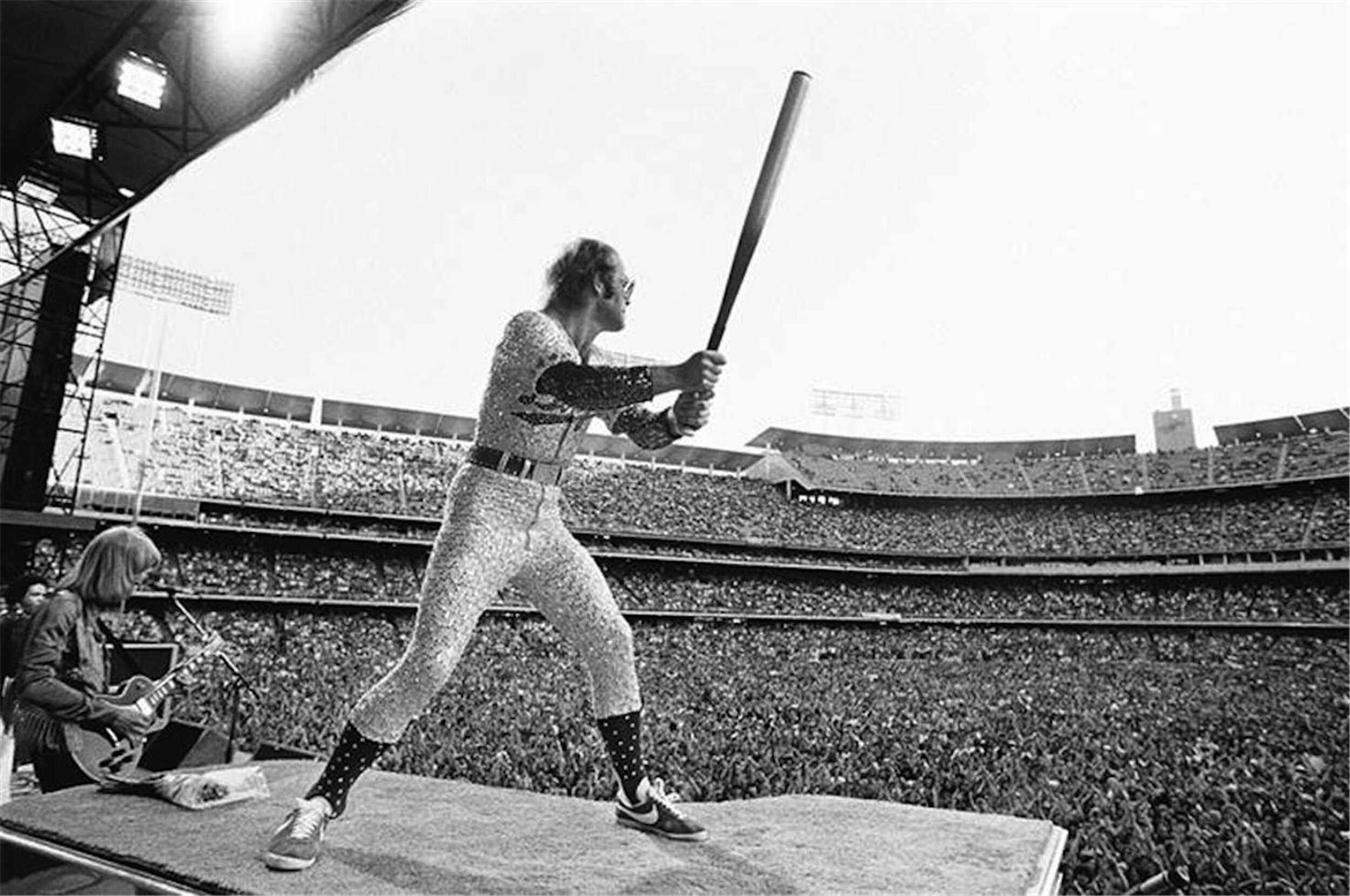

Elton John @ Dodger Stadium - photo by © Terry O'Neill, 1975

Elton John and touring jet 1976 - photo by Sam Emerson

By the time I did several lengthy interviews with Gus in 2002, he and I had spent hours on the phone yakking about whatever came to our minds, which was usually music-related. What follows are some parts of one transcript I found where we talking about his production and mixing philosophy. Keep in mind that we are discussing work primarily done in the ‘70s. Even though Gus was very familiar with computerized mixing, he clearly had a fondness for the old analog way of doing things. I love how he describes old-school manual mixing as “hand-cranked.” A lot of what follows will be of more interest to hardcore Elton fans who are studio geeks. That said, there is a lot of fun stuff in here and it was a pleasure riffling through all these pages of transcript and remembering these conversations.

I’ve provided some great videos I dug up and Gus, Elton, and others discussing those times in the studio. They are well worth watching.

I could do a number more of these Gus Dudgeon installments, but I have one more on the runway that I will share where he talks about his time at Olympic Studios, The Zombies, The Bonzo Dog Band, John Kongos, Audience, XTC and other experiences.

Rick Clark: One of the defining qualities of those great early Elton albums were those huge orchestral arrangements. The had a rock punch. Tracks like "Levon" and Tiny Dancer"…

Gus Dudgeon: "Levon," I think, is one of Paul's best arrangements of all time. That orchestra riff on the outro is fantastic.

Rick Clark: Trying to balance out all the elements, carving out the EQ on the piano, drums, vocals, the strings, and all of that stuff, takes real finesse. Everything has to occupy a space. Choosing the right amount of reverb, so the elements have definition and expansiveness, was also a real trick for this kind of enormous ensemble sound.

Gus Dudgeon: Rick, don't forget the amount of reverbs we had available to us were very slim. I think there were a couple of EMT 240 Gold Foil verbs and maybe two or three EMT 140 Sheets, and that would have been it. You didn't have much control over them.

About the most you could do was EQ the sound on the way into the Sheets and re-EQ it on the way back and set the delay. Anything between half a second and three and a half was maximum. That was as far as you could go. They were great pieces of equipment. They were designed to do precisely what they did, which is to sound good no matter what you put into them.

Rick Clark: And the quality of what you put into them is defined by the performances. I always look for the "accidents" or unplanned magical moments to make the music more alive.

Gus Dudgeon: Right! There's an excellent example of a magic moment from the Madman sessions. It was when Barry Morgan, the drummer on "Levon" played the drum fill in the wrong place, and it was fabulous. It was during Take Three or Four, and he misread the chart. Barry accidentally jumped down a complete line and carried on playing even though he realized what he'd done. He played a written drum fill in the wrong place. When Barry came up to the control room to listen to the playback, I was grinning my head off. I said, "Barry, that was a fucking brilliant drum fill. What on earth made you put it there?" He said, "Oh man, I'm really sorry. I screwed up." I said, "Barry, it was a moment of genius." He said, "No. No. We'll have to do another take." I said, "No way, you've got to hear it." So we played it back, and everybody thought it was brilliant. And he was like, "Are we going to do another take?" I'm going, "No." And he's going, "Come on, guys. We have to do another take." And we're going, "No." The only reason it bothered him was that he knew he'd made a mistake, but it was a fucking brilliant mistake. That doesn't happen if you are programming music. Then it is all coming from one person's point of view and not from a dozen or more people. There are no surprises. There are no happy accidents.

Rick Clark: Madman Across the Water was the zenith of that larger-than-life sound. The follow-up album, Honky Chateau, was an earthy, folky, funky kind of effort.

That started a whole different thing, really. That’s when we went to France for the first time because Elton was being advised by accountants to record abroad, but more importantly, to write the songs abroad, he wouldn’t be paying English tax. I asked to see if I could find something in France and I’d almost given up when somebody tipped me off to Chateau d’Herouville where the Grateful Dead just did an album. As soon as I saw it, I went, “Yeah, this has to be the place.” And it turned out to be, as luck would have it, a very successful choice.

Rick Clark: Goodbye Yellow Brick Road also cut there.

Yeah. Well, I must admit, the only reason that it became a double album was because we’d been to Dynamic Sounds in Jamaica anticipating to possibly record there, and I just couldn’t get a sound together at all. It was weird. The Stones had just recorded there and they were checking out as we checked in. They told us a few slightly scary stories like don’t open the piano lid too fast or you’ll upset the cockroaches that live in there — things like that. It took me three days to get a decent drum sound, and eventually we said, “This isn’t going to work.” So we said, “Let’s go back to the Chateau. We know we can work there and it will be fine.”

Now at this stage, Elton would write all of the songs for each album in the studio during the five days beforehand. He already had an album’s worth of songs together that he wrote right before we started recording in Jamaica. But when he arrived at the Chateau, he felt like writing some more songs. It was like starting another album project. So he wrote some more songs, and all of a sudden, we had more than a double-album’s worth of material. It was only because he wrote two albums — one after the other — because we cancelled the first one. So if we had gone to Jamaica and the sessions had been successful, it would have been a single album. I’m pleased to say that it still is his most successful album.

Rick Clark: I remember being swept away by “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” the first time I heard it. That song always felt like it always existed, sort of like how David Bowie's "Life on Mars" makes me feel.

Gus Dudgeon: Well, what I regret about a lot of today's music is lack of personality. That album is just chock full of personality. It's real performances and real playing, and you know that there are no click machines. Consequently, anything that's any good that is on it is down to the individual's ability on his particular instrument.

Rick Clark: I've always liked the way harmony or background vocals worked on some of those Elton albums.

Gus Dudgeon: Thanks. If you listen to the number of backing vocals on the average Elton John album, there's a lot of it, and it is all top-notch. And a lot of it took a lot of time and hard work, but every second of it was a buzz. All the time we were doing those backing vocals . . . every time we finished a chorus . . . we'd go, "Whew! That was bloody hard work!" You know we might've worked five hours down the line on that section, and then we go right, "Next chorus!" But of course, what happens on the next chorus, cause we'd been around it on the first chorus, as we now had a method of doing it. We'd know which part went on first, which part went on second, blah, blah, blah. But every single part was sung again. Everything.

Rick Clark: Everything. And it had it's own anomalies?

Gus Dudgeon: Of course it did, yes.

Rick Clark: All that time wasted on imperfection!! You could’ve simply flown tracks around. (laughs)

Gus Dudgeon: (laughs) No! That's so boring. Lazy, and it's cheap. It is only done cause there is gear around that is able to do it. And then there is autotune! Come on!

And another thing I hate is that most people's stereo records are just very large monos. There's a guitar on the left, so well, we better put one on the right. Why? What's wrong with the solo coming out of one side? If it sounds good there, put it there! Why is the solo always in the middle? How boring is that?

Rick Clark: Here’s an idea: we could have a revival of the tambourine as one of the loudest elements in the mix.

Gus Dudgeon: Right?!?! (laughs) Some of the early Motown records had the tambourine was twice as loud as the drums. Which is nuts, but it totally worked.

But you also know that no one went into the control room saying, "Right, I want to make a record today with the tambourines twice as loud as the drums." (laughs) No one did it. It just turned out that way. So for whatever reason, it doesn't really matter. But it doesn't stop it being a hit.

If you listen to the Kinks records, they actually managed to distort acoustic guitars on their hit records. To me, it is extraordinary how an engineer can sit through a distorted acoustic guitar throughout the entire session and the mix. It's completely beyond me. So it's there, but it didn't stop the bloody things from being hits.

Rick Clark: Speaking of mixes. Tell me a little about your methodology or challenges at the time.

Gus Dudgeon: When I used to do mixes with Elton, we often had three people sitting on the board, me, the engineer, and usually the tape jockey leaning over the top of the desk, who's job was to pan something from one side to the other, or hit an EQ button, or switch a reverb on for a few seconds or switch it off again. We always used to sit there saying, "God wouldn't it be great if you could have an automatic third hand?" Well, the computer became the third hand, so to speak. But the problem with a computer mix is, you start off making it dynamic, and then you'll notice for instance, that you've lifted a drum fill and you go OK, and so you play it back several times, and then you think well actually that drum fill I've lifted sounds great, but there's this really nice little bass line out there that's getting lost, and actually, the high hat is kinda getting lost at that point as well. And maybe there's a tambourine running through it, so you think at that point the tambourine could come up just a tad to keep pace with the drums. By the time you've finished, the dynamic has been flattened out again. For me, computer mixing is a confidence chase. You can do too much, so consequently, you do it all. That, for me, is the problem.

Rick Clark: Before computerized mixing came along, you had to have done your share of editing with a razor to arrive at some of your final mixes.

Gus Dudgeon: I used to do all my own editing. Having done God knows how many thousands of edits at Decca, it's one of those things I'm actually particularly good at doing.

For example, I would do six or eight mixes of a song, and then when I thought I had maybe a couple of mixes that were 99% of the way there, I'd look for the bits I never quite got right and simply cut in a better section from another take. That's what I did throughout the Captain Fantastic album as well as all those Elton albums back then.

I used to do the same with multi-track recording as well. If you did half a dozen takes, and there was one take that happened to be kind of shitty, but it had a great middle section, I would cut it into the other takes. I'd just cut the best bits together, obviously doing razor blade edits. OK, the risk, of course, is if you fucked the joint up, undoing it and trying to put it back together again could be a bloody nightmare. But that's the risk you take. You're just very, very careful when you edit.

Rick Clark: No, shit!

Gus Dudgeon: (laughs) There's nothing to touch that moment when the red light turns on. And the guy starts counting it in. And you sitting there, waiting for the moment when it happens and you think what's going to happen? It could be a false start or a great start and then fall to pieces in the middle. But you might think, "Shit, I've got to have that intro. That intro is fantastic!" So you use that intro and cut it on to another take. Simple as that.

You know, I always forget what I did in a mix cause I never listen to my own work, like most producers. Once I've done it, and it's pressed, and out there, I just cross my fingers and hope for the best, and that's that. I'll occasionally hear a song I did the radio, and suddenly realize, "Oh yeah, I can remember now! I can hear the point at which the drums are pushed up, and the ambiance comes up behind it, and there is this extra sort of ump. Well, that would have been a mixing move I probably decided a split second before it happened. You follow your instinct … how it feels to you, and when you trust that feeling, you usually go, "Oh that really worked a treat!" So you try it again on the next drum fill and then you keep doing that until you get to a point where you've made a mark on the board.

I always used to use chalk marks on the board, as my kind of "that's as far as I'm going to go." And then there'd be another drum fill where you want to do it, and it just isn't hitting the kick quite as hard, so the ambiance has to be pushed, you know, an extra couple of dBs to make up the difference because it's not reaching into the room in the same way.

All those early mixes of Elton's, before I got anywhere near a computer, are all hand-cranked, and I loved working that way! I much prefer them to quite honestly anything I've really done on computer since. Anything I do on a computer, I just wind up dicking around with things forever and driving myself mad.

Rick Clark: What are the qualities you look for when you are checking out an artist as a producer?

Gus Dudgeon: Wow. If an artist or band had the balls, the songs, and the attitude of say Credence Clearwater or something, I would jump out of my chair to do it. Something that doesn't require three million overdubs. Something where the passion and the clout are all within those four peoples' ability to do it. It doesn't have to be stacked up vocals. It would be something where needing ProTools is irrelevant, where technology is irrelevant quite frankly (laughs). People just go in looking for a good sound and go in and play.

Rick Clark: Like a real band.

Gus Dudgeon: (laughs) Yeah, remember them? Like this decade's Booker T. or Little Feat. Real players who write great songs and just play. They are what they are and have personality — unique in their own personal way.

Rick Clark: Many creatives succumb to second-guessing their work, and soon fear creeps in and sabotages the very thing that could make them genuinely connect.

Gus Dudgeon: Absolutely. There are very few people who are actually prepared to back their uniqueness to the hills. They are all looking at what somebody else is doing. They make sure that they combine some aspects of what everybody else is doing rather than having the spunk to go out and do precisely what they really want to do without paying attention to what is fashionable. It is a question about finding people that couldn't give a toss about any of that. They just want to get in and cut a record.

I recently did this Danish artist. We had a good collection of songs, a great singer, and excellent musicians. We had the right ingredients, and it was his biggest album. Everyone brought the goods, and it was a pleasure. The trouble with Denmark is a gold album is 25,000 units.

We can sit here and have the same conversation that I'm sure you've had with 101 other people in the music business about the state of the industry today. And then along comes something like O Brother Where Art Thou! And, Christ, look at the sales of that album! It's not like it came from a hugely successful movie. I imagine the CD is, in terms of the ratio of success, more significant than the film itself. It's stuffed full of great music and technology hasn't gone anywhere near it.

Rick Clark: It's got that thing you said called feel.

Gus Dudgeon: Yeah. It only goes to show that there's an audience for it. Thank God there is. But what happens is everybody applauds everybody that was involved in it. Still, the executives don't go back to their office and say, "You know, we should learn a lesson from this." They don't. They go back to their office and listen to something that's machine-driven, and if it doesn't sound like it's got a hit song attached to it, they drop it, or they don't sign it. It's quite weird.

Elton and Gus Dudgeon talk about his fast song writing in 1973, during the making of "Goodbye Yellow Brick Road." He wrote and recorded four songs a day, plus vocals, 2:26. So...

Elton John and Ms. Piggy on Sesame Street

Elton John and Gus Dudgeon at Console